Conceptual-themed Illustrations: What Life, a War Orphan’s Memory

For my visual thesis, I created a series of ten conceptual illustrations that were showcased in my final thesis exhibition. These illustrations depict the life stories of war orphans, which serve as poignant examples of the pain inflicted by war. Through my artwork, I hope to prompt deep reflections on the cruelty of war and evoke an emotional resonance with the experiences of war orphans among my audience.

In conceptualizing my art project, I likened the process to that of nurturing and giving birth to a child. Just as a human body requires a structural skeleton, I utilized Erik Erikson’s theory of the 8 Stages of Psychosocial Development to analyze the life stories of war orphans. This allowed me to portray their psychological transformations at different stages of their lives. Building upon this metaphorical framework, I infused my artwork with “muscles” by creating a new character based on extensive research from historical materials and non-fiction books that I collected. While each war orphan had a unique story, I aimed to distill their collective experiences into the narratives of the characters depicted in my artwork. My intention is for these characters to represent the broader life experiences of war orphans, enabling viewers to develop a deeper emotional understanding of their struggles. Ultimately, my goal is to enlighten individuals who may be unfamiliar with this history and foster an empathetic connection to the plight of war orphans through my artwork.

In psychiatrist Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, there are eight stages that encompass a person’s life from infancy to late adulthood. These stages represent different challenges that individuals encounter and overcome as they progress. While Mr. Erikson acknowledged the significance of early childhood experiences, he also emphasized the role of the social environment in an individual’s development. In my final ten illustrations, I attempted to apply Mr. Erikson’s theory to analyze the social and psychological formation process of war orphans.

To depict this comprehensive narrative, I created ten illustrations corresponding to different stages of the war orphans’ lives. Each illustration was accompanied by a text description to enhance the viewer’s understanding. Through the combined use of visual illustration art and literature, I sought to immerse the audience in the vivid life stories of war orphans.

Historical advisors:

- Dr. Srivi Ramasubramanian | Professor | S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications

- Hanayo Oya | Assistant Professor | S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications

- Dr. Nini Pan | Associate Professor | East China Normal University

“I was an infant whose upbringing was shaped by both China and Japan, and my life story intertwines with the rich histories of these two countries. Today, I would like to share with you my extraordinary journey through life“

“After Japan’s defeat in World War II, the Kwantung Army abandoned the Manchurian pioneer group, leaving my Japanese mother with no choice but to flee from China in a state of panic. Amidst the chaos, I was unintentionally separated from her and left behind in Northeast China. However, fortune smiled upon me when I was taken in by a kind-hearted Chinese farmer couple, who not only saved my life but also showered me with love and care“

For the first and second illustrations of the thesis, I focused on portraying the initial stage of Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Development Theory: Trust vs. Mistrust, Infancy (0-2 years old). According to Erikson’s theory, parents play a crucial role in establishing trust during this stage. However, most war orphans lacked the presence of their Japanese parents and were still adjusting to their Chinese adoptive parents. Trust can only develop in a secure environment. In my first illustration, I symbolized Japan and China with a chrysanthemum and a peony respectively, while depicting the significant bond between the infant and parents as a womb with an umbilical cord. In the second illustration, I utilized a Chinese woman’s shoe and a peony to represent the Chinese family. I depicted a fetus lying in an oyster to symbolize rebirth and incorporated a pomegranate to convey the traditional Chinese cultural belief in many children and blessings, as war orphans were often adopted by families unable to have their own sons.

“My memories of childhood were hazy and elusive. I remember engaging in playful activities with various toys but distinguishing between those given by my Japanese biological mother and those bestowed upon me by my Chinese adoptive mother proved challenging“

In the third illustration, which corresponds to Erikson’s second stage of development (Childhood) for children aged 2-3 years, I focused on the theme of Autonomy versus Shame and Doubt. During this stage, children begin to assert their own will and often imitate their parents’ behaviors through play. For war orphans, their childhood stage was marked by significant change, transitioning from their Japanese families to Chinese families, especially during the chaotic period at the end of World War II. Many war orphans have fragmented and disordered childhood memories. In my third illustration, I depicted a combination of traditional Chinese and Japanese toys to symbolize the war orphans’ jumbled childhood memories.

“During my preschool years, my days were filled with adventurous exploration of the vast farmland that surrounded our home. I was captivated by the unique plants and insects that thrived there, often daydreaming about joining them in their miniature world. While I enjoyed the company of children my age, I couldn’t help but notice our differences, particularly in my Chinese language skills. This realization sometimes left me feeling scared and bewildered. However, I found solace in the unwavering support of my Chinese adoptive parents. They stood by my side, shielding me selflessly from any harm that may have crossed my path“

The fourth illustration introduces Erikson’s third stage of development (Initiative versus Guilt) for the preschool age group (3-6 years old). During this stage, children’s primary mission is to gain recognition. For most war orphans, it was during this time that they started interacting with other Chinese children, which brought about identity confusion as they realized their differences. Many war orphans felt a sense of loneliness, confusion, and fear. In my fourth illustration, I portrayed a war orphan imagining himself as an insect, seeking companionship with insect friends as a way to cope with the challenges of feeling different from other Chinese children.

“Despite facing financial challenges, my adoptive parents devoted all their savings towards funding my education. I enrolled in an ordinary Chinese elementary school and began my studies like any other student. I considered myself lucky to have been enveloped by the selfless love and protection of my adoptive parents“

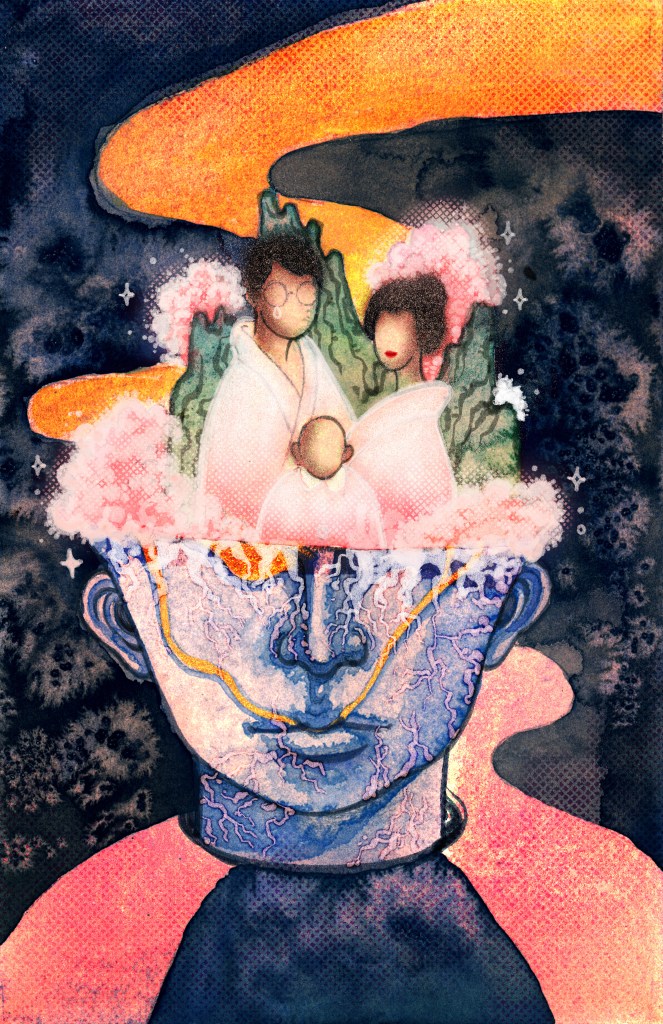

In the fifth illustration, I depicted Erikson’s fourth stage of development, Industry versus Inferiority, which applies to school-aged children (6-12 years old). During this stage, the significant relationship for children is their school. Many war orphans experienced discrimination from their Chinese peers, but they found support and protection from their Chinese parents and teachers. In my fifth illustration, I portrayed the war orphan embracing their Chinese parents to symbolize their mutual support and solidarity.

“During my adolescence, a significant socialist transformation swept through the cultural landscape, impacting all Chinese individuals of my generation. It was a time when teenagers were brimming with enthusiasm, some might even say they were a bit “crazy”. We opposed all forms of privilege and traditional authority within society. In schools, students fearlessly questioned and challenged the views of professors, even if it meant the closure of schools and the suspension of classes. This collective memory of adolescence remains deeply ingrained in the hearts of all Chinese individuals of my generation“

The sixth illustration represents Erikson’s fifth stage of development, Identity versus Role Confusion, which pertains to adolescents (ages 13-19). During this stage, teenagers’ significant relationships revolve around their peer groups. For war orphans, their adolescence coincided with the tumultuous 10 years of the Great Cultural Revolution in China. This period held immense significance in modern Chinese history and became a collective memory for all Chinese people. In my sixth illustration, I incorporated a peony to symbolize China, while using a star and a red ribbon to represent socialism. I opted for an ink drawing style to emulate the woodcut style prevalent in Cultural Revolution-era posters.

“Being adopted by Chinese parents at a young age, I have lived a life akin to that of an ordinary Chinese person. While I faced various economic and daily life challenges, I was fortunate to have a loving family by my side. Regardless of the difficulties we encountered, our family always supported one another. Over time, I have undergone a gradual transformation from being a Japanese child who survived the war to becoming an ordinary young Chinese man today“

“In my early adulthood, China and Japan had restored normal diplomatic relations, leading the government to approach me about the possibility of returning to Japan to search for my biological relatives. Engaging with professional government personnel, I entertained the idea of embarking on a journey to Japan to reconnect with my birth parents for the first time. However, I faced the unfortunate challenge of having blurry memories of my hometown in Japan due to my young age at the time“

The seventh and eighth illustrations depict Erikson’s sixth stage of development, Intimacy versus Isolation, which characterizes early adulthood (ages 20-39). During this stage, individuals strive to form close relationships and navigate the joys and sorrows of life together. For many war orphans, early adulthood marked the transition from being a young Japanese child to becoming an ordinary Chinese adult. Additionally, with the resumption of normal diplomatic relations between China and Japan in 1952, war orphans had the opportunity to return to Japan in search of their lost relatives. However, due to their age, many war orphans had difficulty recollecting clear and useful information about their Japanese families, which posed challenges in their search. In my seventh illustration, I utilized an egg as a powerful symbol, representing the metamorphosis from a young Japanese boy to an ordinary Chinese adolescent. In the eighth illustration, I employed the Japanese traditional handicraft technique of Kintsugi to symbolize the process of piecing together fragmented memories.

“In my middle adulthood, I made the courageous decision to embark on a challenging journey to Japan in search of my long-lost biological relatives. However, the path I walked was filled with numerous obstacles and difficulties, and the reality of finding my family proved to be far from easy. Sadly, many war orphans like me encountered similar hardships along the way. Having spent the majority of my life in China, adapting to Japanese culture and society posed significant challenges, especially given my limited proficiency in the Japanese language. This made it difficult for me to secure employment beyond low-income manual labor. Despite my

Japanese heritage, I faced prejudice and a lack of acceptance from many individuals, leaving me caught between my Chinese and Japanese identities. The resulting confusion and inner turmoil weighed heavily on my heart, intensifying over time“

In the ninth illustration, I presented Erikson’s seventh stage of development, Generativity versus Stagnation, which pertains to middle adulthood (ages 40-64). During this stage, adults’ significant relationships encompass their social community and family. In the middle adulthood of many war orphans, they made the decision to return to Japan in search of their relatives. However, they encountered difficulties reintegrating into Japanese society due to their age. Many war orphans faced identity issues upon their return, struggling with language barriers as they were too old to relearn Japanese. Additionally, cultural barriers emerged as they had spent the majority of their lives in China. Some war orphans found themselves with no alternative but to join organized criminal gangs, such as the second-generation Japanese war orphans’ organized criminal gang known as “Doragon”. In my ninth illustration, I utilized plants and insects as symbols of identity confusion. Masks, mouths, and eyeballs were incorporated to represent their fear of being subjected to gossip.

“As I reached old age and reflected on my life, I realized that I had always existed in the space between China and Japan. Recalling my extraordinary journey, I often wondered if I truly belonged to either country. Instead, I considered myself as a child of the Earth, transcending borders and nationalities. What led me to endure such a unique path? It was the devastating impact of war. Without the horrors of war, perhaps I would have spent my entire life peacefully with my family in a rural village. If not for war, I would not have experienced the loss of my relatives, and my life story would have taken an entirely different course. Yet, these were mere musings and wishes. War has a cruel way of uprooting and reshaping the lives of ordinary civilians. By sharing my experiences, I aspire to foster greater understanding among people worldwide about the immense suffering caused by war. Above all, I yearn for a world of peace, where future generations will be spared from enduring the same pain and loss that I have witnessed and endured“

The tenth illustration depicts Erikson’s eighth and final stage of development, Ego Integrity versus Despair, which applies to old age (ages 65 years and beyond until death). During this stage, the primary task for older individuals is to reflect upon and accept their life’s journey. In my tenth illustration, the war orphan has become an elderly man, contemplating his life. I intentionally incorporated the same design elements of a chrysanthemum and a peony from my first illustration, creating a visual echo between the two. Furthermore, I deliberately chose a smaller size of 11″x15″ for the tenth illustration compared to the other nine pieces. This was a deliberate decision to give this final artwork a distinct significance, serving as a punctuation mark to my project and symbolizing the conclusion of the war orphan’s life story.

Reflecting on the life stories of these aging individuals, I realized they had endured the cruelty of war, witnessed the complexity of human nature, experienced the warmth of love, and encountered numerous stumbling blocks throughout their lives. They were individuals whose lives were permanently influenced by the effects of war. It is crucial that we strive to prevent any future conflicts. Let us not allow the forthcoming generations to experience the horrors of war. This very reason compelled me to choose this topic as the focus of my thesis. Additionally, I aspire to share more authentic Asian narratives with English-speaking audiences. Finally, let us come together to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II and pray for eternal peace for all people around the world.